Limbal cell transplants

Success of limbal cell transplantation continuing to improve

Priscilla Lynch

Published: Sunday, March 1, 2020

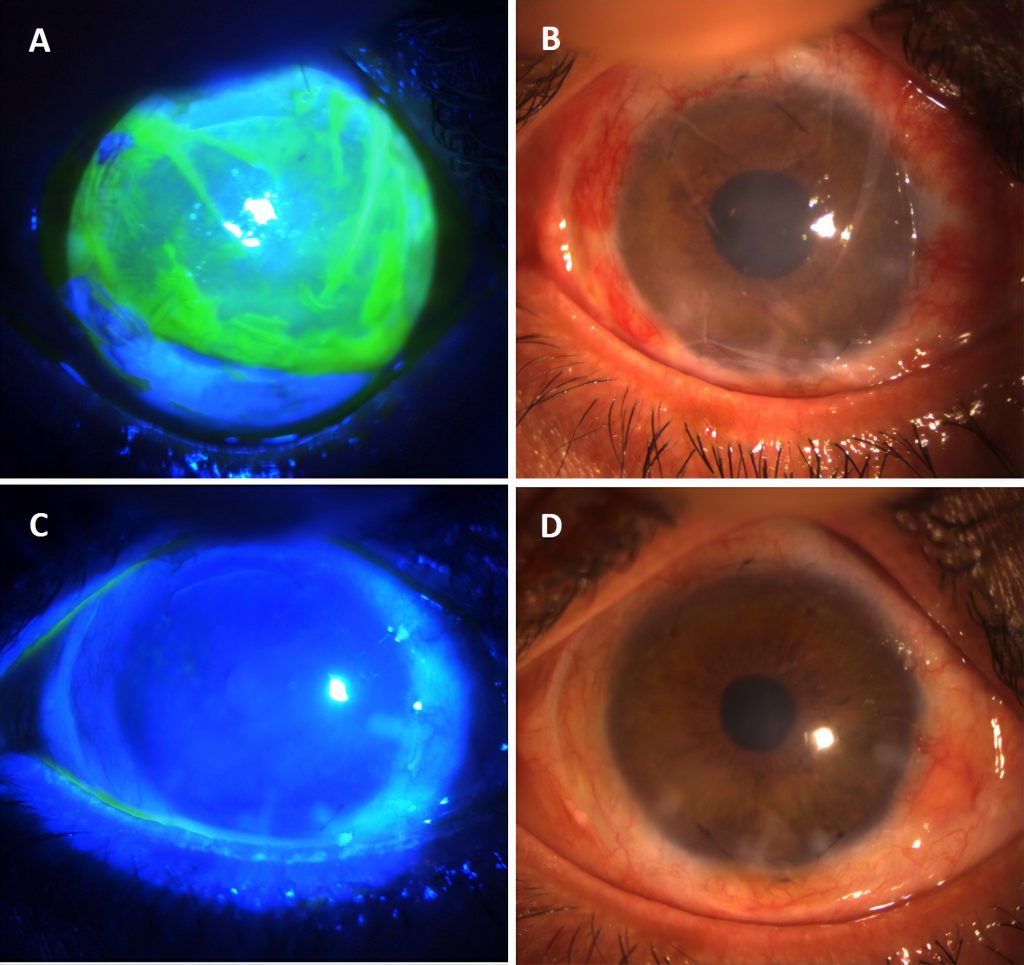

Amnion-assisted conjunctival epithelial re-direction in limbal stem cell transplantation. A. Vacuum-dried amnion (Omingen), fluorescen stained and B. without fluorescein stain is shown covering the limbal explants at 12 and 6 o’clock positions. The amnion is tucked under the peritomised conjunctiva along the circumference. This forces conjunctival epithelium to grow on the amnion, leaving the limbal explant derived epithelium to cover the cornea without conjunctivalisation as seen in C. with fluorescein stain and D. without fluorescein stain, after removal of the amnion on week 3.

Image courtesy of Courtesy of Harminder Dua, CBE, MD, PhD

The success of limbal cell transplantation for treating non-healing corneal ulcers continues to improve due to advances in the stem cell supports for this procedure, according to Harminder Dua, CBE, MD PhD, University of Nottingham, Queen’s Medical Centre, Nottingham, UK.

Addressing the potential of corneal-limbic keratoplasty during a dedicated session on non-healing corneal ulcers at the 10th EuCornea Congress in Paris, France, Prof Dua noted that “limbal cell deficiency is a very important cause of non-healing corneal ulcers”, with transplantation regularly indicated to restore normal corneal epithelium in these cases.

The source of cells and tissue for treating non-healing ulcers includes the limbus, but also the conjunctiva, Buccal mucosa and mesenchymal cells, he explained.

Looking at limbal cell transplantation techniques, he said the main objective is to cover the ulcer with cells from the source tissue, with two main approaches used: in-vivo expansion and ex-vivo expansion. “Both require a good substrate for cells to grow on, from where you transfer them to where you want them to be… and these substrates can be natural basement membranes, natural proteins and synthetic polymers,” Prof Dua said, going on to discuss the benefits of each option.

Outlining the use of amniotic membrane as a support structure for stem cells in transplantation, the latest approach involves modified human amnion that has been gamma-radiated and decellularised with sodium dodecyl sulfate or low heat vacuum dried amniotic membrane without spongy layer (Omnigen) which are efficient substates for the ex-vivo expansion of limbal stem cells, and have certain advantages but also some limitations such as limited flexibility and early dissolution,

he said.

Looking at the use of biopolymers, Prof Dua said fibrin sheet technology “is the most well-tested biopolymer and is used as the substrate in the only licenced stem cell product in the world so far (Holoclar)”, while with gelatin sheets, “it has been shown you can increase the roughness, stiffness and integrin 1 expression, metabolic activity and ABCG2 expression, and improve the ability of the cells to grow and attach better to the substrate” during transplantation.

“These are things that are being worked on and it is likely that we will eventually have synthetic polymers; there is a lot of work going on with this, and these are very biocompatible,” and could have many customised benefits, he noted.

In summary, Prof Dua said that natural (same site, orthotopic) in-vivo substrates support stem cells best. Natural (non-same site, heterotopic) substrates also support stem cells well, amnion being the most popular. While biopolymers have several advantages, synthetic polymers are likely to be the future, he concluded.

Harminder Dua: profdua@gmail.com

Amnion-assisted conjunctival epithelial re-direction in limbal stem cell transplantation. A. Vacuum-dried amnion (Omingen), fluorescen stained and B. without fluorescein stain is shown covering the limbal explants at 12 and 6 o’clock positions. The amnion is tucked under the peritomised conjunctiva along the circumference. This forces conjunctival epithelium to grow on the amnion, leaving the limbal explant derived epithelium to cover the cornea without conjunctivalisation as seen in C. with fluorescein stain and D. without fluorescein stain, after removal of the amnion on week 3.

Image courtesy of Courtesy of Harminder Dua, CBE, MD, PhD

The success of limbal cell transplantation for treating non-healing corneal ulcers continues to improve due to advances in the stem cell supports for this procedure, according to Harminder Dua, CBE, MD PhD, University of Nottingham, Queen’s Medical Centre, Nottingham, UK.

Addressing the potential of corneal-limbic keratoplasty during a dedicated session on non-healing corneal ulcers at the 10th EuCornea Congress in Paris, France, Prof Dua noted that “limbal cell deficiency is a very important cause of non-healing corneal ulcers”, with transplantation regularly indicated to restore normal corneal epithelium in these cases.

The source of cells and tissue for treating non-healing ulcers includes the limbus, but also the conjunctiva, Buccal mucosa and mesenchymal cells, he explained.

Looking at limbal cell transplantation techniques, he said the main objective is to cover the ulcer with cells from the source tissue, with two main approaches used: in-vivo expansion and ex-vivo expansion. “Both require a good substrate for cells to grow on, from where you transfer them to where you want them to be… and these substrates can be natural basement membranes, natural proteins and synthetic polymers,” Prof Dua said, going on to discuss the benefits of each option.

Outlining the use of amniotic membrane as a support structure for stem cells in transplantation, the latest approach involves modified human amnion that has been gamma-radiated and decellularised with sodium dodecyl sulfate or low heat vacuum dried amniotic membrane without spongy layer (Omnigen) which are efficient substates for the ex-vivo expansion of limbal stem cells, and have certain advantages but also some limitations such as limited flexibility and early dissolution,

he said.

Looking at the use of biopolymers, Prof Dua said fibrin sheet technology “is the most well-tested biopolymer and is used as the substrate in the only licenced stem cell product in the world so far (Holoclar)”, while with gelatin sheets, “it has been shown you can increase the roughness, stiffness and integrin 1 expression, metabolic activity and ABCG2 expression, and improve the ability of the cells to grow and attach better to the substrate” during transplantation.

“These are things that are being worked on and it is likely that we will eventually have synthetic polymers; there is a lot of work going on with this, and these are very biocompatible,” and could have many customised benefits, he noted.

In summary, Prof Dua said that natural (same site, orthotopic) in-vivo substrates support stem cells best. Natural (non-same site, heterotopic) substrates also support stem cells well, amnion being the most popular. While biopolymers have several advantages, synthetic polymers are likely to be the future, he concluded.

Harminder Dua: profdua@gmail.com

Tags: limbal cell transplantation

Latest Articles

Overcoming Barriers to Presbyopic IOL Uptake

Improving technology, patient and doctor awareness, and reimbursement are keys.

Training in the Digital Era

AI-powered, cloud-based system can effectively improve traineeship, save time, and increase performance.

Treating Myopia, Inside and Outside

Lifestyle changes and ophthalmic interventions play a role in treating paediatric myopia.

The Promises and Pitfalls of AI

While AI shows potential in healthcare, experts agree it requires bias mitigation and human oversight.

Visual Rehabilitation for Keratoconus

Concepts regarding best techniques shift based on learnings from longer follow-up.

Discovering Prodygy and Nirvana

New gene-agnostic treatments for inheritable retinal disease.

Cataract Surgery in Eyes with Corneal Disease

Applying information from preoperative diagnostics guides surgical planning.

Supplement: Integrating Presbyopia-Correction into the Everyday Cataract Practice

ESCRS Research Projects Make a Difference

EPICAT study continues tradition of practice-changing clinical studies.