Cornea, Corneal Therapeutics

Treating Fungal Keratitis

Off-label compounded agents serve as alternatives for managing myopic infections.

Cheryl Guttman Krader

Published: Thursday, August 1, 2024

The corneal specialist can represent the final line of defence for helping patients with fungal keratitis avoid painful loss of vision, and fulfilling this role requires maintaining an emergency armoury of antifungal medications for in-office compounding, according to Dean Ouano MD.

“I am sensitive to the realities of medicolegal liability and regulatory issues associated with compounding topical medications, but ultimately, our responsibility is the care of our patients,” Dr Ouano stated. “Safe office preparation of topical antifungals is possible and, I would argue, necessary if we are the last line of defence.”

Outlining the options

Reviewing the agents used for medical fungal keratitis treatment, Dr Ouano noted natamycin 5% is the only commercially available ophthalmic antifungal medication. Its consideration as first-line therapy for infections caused by filamentous fungi is supported by results of the Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial, which found it superior to voriconazole monotherapy.1 Natamycin is not available in oral or intravenous forms and cannot be compounded for subconjunctival or intrastromal delivery.

Combined use with voriconazole can provide synergistic or additive antifungal activity, according to data from in vitro testing. Voriconazole remains the most widely used compounded antifungal for treating fungal keratitis since it is reasonably priced, easily formulated, and well-tolerated given topically or when injected into the stroma, anterior chamber, or vitreous. However, fungal resistance to voriconazole and other newer generation triazoles has become a problem secondary to widespread use of triazoles as agricultural fungicides, Dr Ouano said.

Posaconazole, a newer triazole, has been associated with some encouraging results for treating filamentous fungal keratitis when used at a high oral dose. However, this regimen carries a high cost, risks of liver and cardiac toxicity, and the potential for multiple interactions with medications metabolised by CYP3A4.

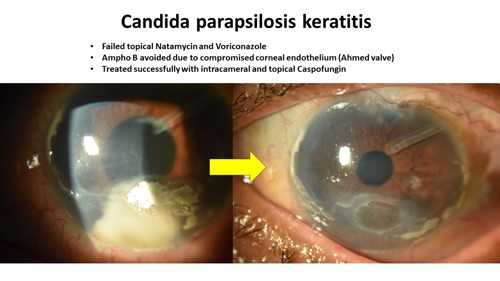

Amphotericin B is generally regarded as the drug of choice for Candida infections—although Dr Ouano said he prefers not to use it considering its inherent intraocular toxicity, which includes retinal ganglion cell loss, vitreal inflammation, and corneal oedema.

“Lipid-based formulations of amphotericin B are not necessarily less toxic,” he added.

Limited experience shows encouraging results using echinocandin agents to treat fungal keratitis. Caspofungin and micafungin are the two clinically useful drugs in this newest class of antifungals. Caspofungin can be compounded for topical or intraocular administration, but there is limited data on the use of micafungin for intraocular use.

Echinocandins are safer than triazoles because they target fungal cell walls selectively and have fewer drug interactions. In addition, they are fungicidal against Candida, making them more effective than the fungistatic triazoles. The echinocandins are also fungistatic against Aspergillus, albeit less effective than polyenes against Fusarium and Cryptococcus due to their mechanism of action.

Most reports of echinocandin treatment for fungal keratitis involve compounded caspofungin, which can be easily prepared as a solution for topical use at a reasonable price. As another advantage, the preparation remains stable for up to four weeks when kept refrigerated.

Micafungin may be more cost-effective than caspofungin, but there are fewer published reports on its use for treating fungal ocular infections. However, Dr Ouano cited one case series from Japan describing topical micafungin for treating refractory yeast-related corneal ulcers and reported his own positive experience using it to treat fungal keratitis and fungal-positive donor corneal rims.2

Dr Ouano spoke during ASCRS 2024 Cornea Day in Boston, US.

Dean P Ouano MD specialises in glaucoma, cataract, and cornea surgery at the Coastal Eye Clinic, New Bern, North Carolina, US. ddouano@gmail.com

1. Prajna NV, Krishnan T, Mascarenhas J, et al; Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial Group. “The mycotic ulcer treatment trial: a randomized trial comparing natamycin vs voriconazole,” JAMA Ophthalmol, 2013; 131(4): 422–429.

2. Matsumoto Y, Dogru M, Goto E, Fujishima H, Tsubota K. “Successful topical application of a new antifungal agent, micafungin, in the treatment of refractory fungal corneal ulcers: report of three cases and literature review,” Cornea, 2005; 24(6): 748–753.