Dealing with complications

Soosan Jacob MD says when travelling the road from initiation to becoming a seasoned ophthalmologist, YOs should not be disheartened by complications

Soosan Jacob

Published: Tuesday, July 9, 2019

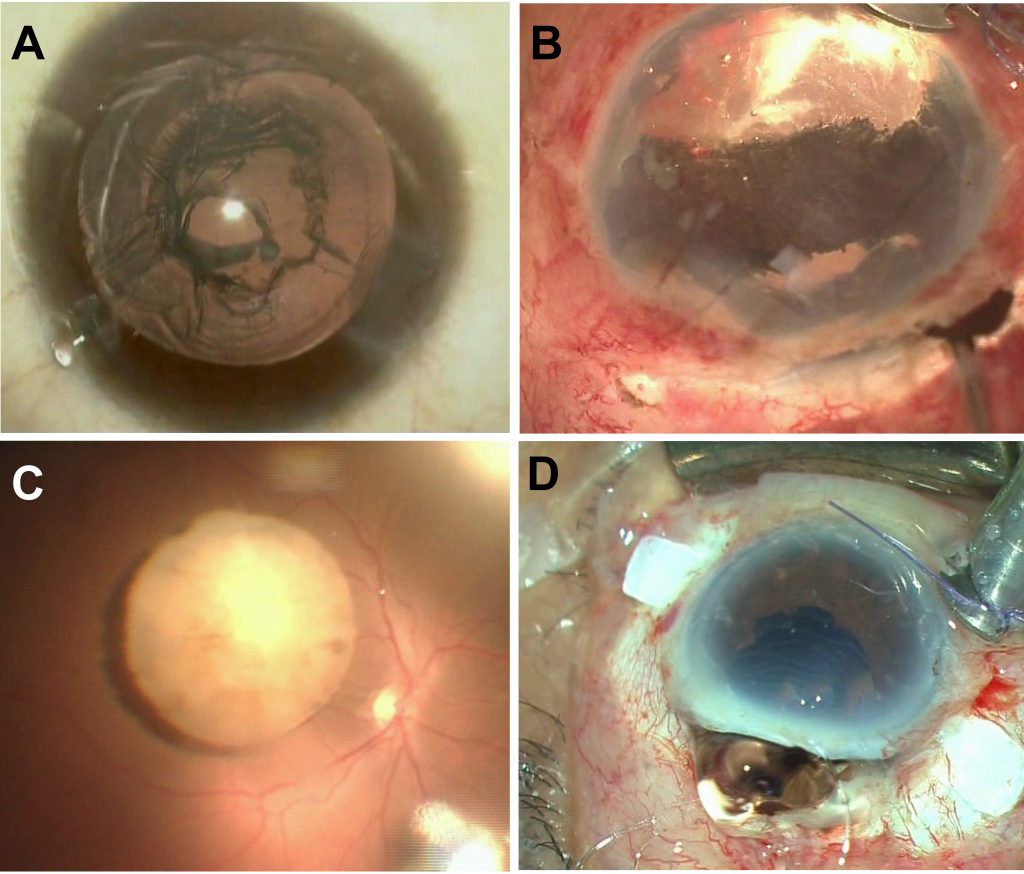

A: Posterior capsule rupture; B: Iridodialysis; C: Nucleus drop; D: Expulsive haemorrhage

Eugen Bleuler, in a letter to Sigmund Freud in 1911 wrote: “In Science, there is no such thing as unmitigated good.” Lack of efficacy and complications are sometimes the price that not only a young ophthalmologist but even a seasoned one pays. How does one decrease the occurrence of complications and their effects on both patient and physician?

This is a time of mixed emotions – confidence and pride in all that is learnt, fear and dread of all the unknown, a presumed wealth of clinical experience and possible inexperience in handling unexpected surgical scenarios, human emotions and real situations. The euphoria that a job well done gives may be followed by deep misery for a complication, whether avoidable or unavoidable. It is truly a rollercoaster time of emotions.

So how does one smoothly travel the road from initiation into the ophthalmic fraternity to becoming a seasoned ophthalmologist?

The first thing that any YO should do is to embrace the fact that complications will occur. They occur in the best and safest of hands and occur because of controllable and uncontrollable factors. The best way to prevent them is to know them, anticipate them and therefore be prepared for them. Fear of complications is normal but it should not stop one from operating.

Prevention and management of complications comes through a continuous process of self-improvement via theoretical learning, attending conferences, listening to other surgeons share their experiences and tough cases, watching live situations and videos of others, wetlabs and simulations, handheld surgeries, independent surgeries, reviewing of one’s own surgical videos – the entire cycle repeated over and over again. A constant learning process is important to avoid getting trapped in a comfort zone that can prevent skill levels from increasing.

AVOIDING COMPLICATIONS

Preoperatively, take care to go through the patient’s chart, familiarising yourself with the ocular and systemic condition. Talk to the patient to assess if expectations from the surgery are realistic or not and if not, explain to the patient his/ her condition, expected results, possible complications specific to him/ her as well as general complications that can occur. This should be documented in the case sheet as well as via an informed consent sheet signed by the patient. Remember, it is always better to under-promise and over-deliver than the reverse; an informed patient is also better equipped to mentally and emotionally handle any complications.

Appropriate investigations and planning prior to surgery is important. A mental road map should be formulated chalking out the planned, expected route as well as alternate routes that may become necessary in case of any roadblocks. Make sure that all desired drugs, equipment, devices and instruments are available and working well. It is wise to have a patient anaesthetist and nurse assistant who have experience working with trainees and young ophthalmologists.

MANAGING COMPLICATIONS

Never forget a time-out just before surgery to go through the pre-surgical checklist with your team. Intraoperatively, be on watch for situations that can potentially increase risk of complications and treat them if necessary. Don’t try breaking records in speed. Even Usain Bolt had to practise for years before creating records. Most importantly, when facing a complication – do not panic. A classic, oft-quoted example of what not to do is panicking and suddenly withdrawing the I/A probe, accidentally capturing the posterior capsule. Take a moment to reassess and then proceed if confident or call for help.

There is no shame in asking a more experienced and trusted mentor/ colleague for help or handing over for further management. Remember it is the eye that matters and not the “I”.

Sometimes, one may just have to close the case midway and refer the patient for further management, eg in case of a nucleus or IOL drop. Even though this may be a difficult decision in terms of not having finished surgery, remember – it is better to live to fight another day.

It is also important to maintain equanimity and not convey panic to the patient as this can lead to intraoperative stress for the patient that may worsen the situation. In many operating set-ups, patients are not sedated and thereby are awake and intensely aware of everything happening. Under the drape, some patients try and analyse what they hear even up to the tone of voice of the surgeon. Random jokes, shouting, panicking, complaining, expressing exasperation with the system as well as other casual comments should be avoided, especially if the patient is not sedated, as these may result in the patient drawing wrong conclusions about the situation and how it is handled as well as make the patient panicky.

RECOVERING FROM COMPLICATIONS

This applies for both the patient and the YO. Postoperatively, the sense of having got all possible support from the operating surgeon is important, as is having a discussion with the patient about what happened, how it is planned to be managed as well as expected outcomes.

Emotional support to patient and family and arranging for any consults is crucial to help the patient out in the unfamiliar and unexpected territory they find themselves in. This also helps in maintaining a rapport with the patient.

Panic and a demoralised feeling is common for the surgeon too after encountering a complication. Emotional support can often be got from family, friends and mentors and this should be sought for and gratefully accepted. It is important to recover soon from the low after a complication and bounce back. Mentors are an important source of help for advice as well, and it is always important to give thanks to them.

Post-procedural review and analysis to see if the complication could have been avoided or tackled in a faster/ better way is important and this leads to a process of constant self-improvement.

To conclude: do not get disheartened by complications. There is a learning curve for everyone with published data for various procedures. Go step by step to improve your skills. Remember, Rome was not built in a day. And always, even with terrific results, there will be some unhappy patients, as well as deeply grateful ones with suboptimal results.

Dr Soosan Jacob is Director and Chief of Dr Agarwal’s Refractive and Cornea Foundation at Dr Agarwal’s Eye Hospital, Chennai, India and can be reached at dr_soosanj@hotmail.com

A: Posterior capsule rupture; B: Iridodialysis; C: Nucleus drop; D: Expulsive haemorrhage

Eugen Bleuler, in a letter to Sigmund Freud in 1911 wrote: “In Science, there is no such thing as unmitigated good.” Lack of efficacy and complications are sometimes the price that not only a young ophthalmologist but even a seasoned one pays. How does one decrease the occurrence of complications and their effects on both patient and physician?

This is a time of mixed emotions – confidence and pride in all that is learnt, fear and dread of all the unknown, a presumed wealth of clinical experience and possible inexperience in handling unexpected surgical scenarios, human emotions and real situations. The euphoria that a job well done gives may be followed by deep misery for a complication, whether avoidable or unavoidable. It is truly a rollercoaster time of emotions.

So how does one smoothly travel the road from initiation into the ophthalmic fraternity to becoming a seasoned ophthalmologist?

The first thing that any YO should do is to embrace the fact that complications will occur. They occur in the best and safest of hands and occur because of controllable and uncontrollable factors. The best way to prevent them is to know them, anticipate them and therefore be prepared for them. Fear of complications is normal but it should not stop one from operating.

Prevention and management of complications comes through a continuous process of self-improvement via theoretical learning, attending conferences, listening to other surgeons share their experiences and tough cases, watching live situations and videos of others, wetlabs and simulations, handheld surgeries, independent surgeries, reviewing of one’s own surgical videos – the entire cycle repeated over and over again. A constant learning process is important to avoid getting trapped in a comfort zone that can prevent skill levels from increasing.

AVOIDING COMPLICATIONS

Preoperatively, take care to go through the patient’s chart, familiarising yourself with the ocular and systemic condition. Talk to the patient to assess if expectations from the surgery are realistic or not and if not, explain to the patient his/ her condition, expected results, possible complications specific to him/ her as well as general complications that can occur. This should be documented in the case sheet as well as via an informed consent sheet signed by the patient. Remember, it is always better to under-promise and over-deliver than the reverse; an informed patient is also better equipped to mentally and emotionally handle any complications.

Appropriate investigations and planning prior to surgery is important. A mental road map should be formulated chalking out the planned, expected route as well as alternate routes that may become necessary in case of any roadblocks. Make sure that all desired drugs, equipment, devices and instruments are available and working well. It is wise to have a patient anaesthetist and nurse assistant who have experience working with trainees and young ophthalmologists.

MANAGING COMPLICATIONS

Never forget a time-out just before surgery to go through the pre-surgical checklist with your team. Intraoperatively, be on watch for situations that can potentially increase risk of complications and treat them if necessary. Don’t try breaking records in speed. Even Usain Bolt had to practise for years before creating records. Most importantly, when facing a complication – do not panic. A classic, oft-quoted example of what not to do is panicking and suddenly withdrawing the I/A probe, accidentally capturing the posterior capsule. Take a moment to reassess and then proceed if confident or call for help.

There is no shame in asking a more experienced and trusted mentor/ colleague for help or handing over for further management. Remember it is the eye that matters and not the “I”.

Sometimes, one may just have to close the case midway and refer the patient for further management, eg in case of a nucleus or IOL drop. Even though this may be a difficult decision in terms of not having finished surgery, remember – it is better to live to fight another day.

It is also important to maintain equanimity and not convey panic to the patient as this can lead to intraoperative stress for the patient that may worsen the situation. In many operating set-ups, patients are not sedated and thereby are awake and intensely aware of everything happening. Under the drape, some patients try and analyse what they hear even up to the tone of voice of the surgeon. Random jokes, shouting, panicking, complaining, expressing exasperation with the system as well as other casual comments should be avoided, especially if the patient is not sedated, as these may result in the patient drawing wrong conclusions about the situation and how it is handled as well as make the patient panicky.

RECOVERING FROM COMPLICATIONS

This applies for both the patient and the YO. Postoperatively, the sense of having got all possible support from the operating surgeon is important, as is having a discussion with the patient about what happened, how it is planned to be managed as well as expected outcomes.

Emotional support to patient and family and arranging for any consults is crucial to help the patient out in the unfamiliar and unexpected territory they find themselves in. This also helps in maintaining a rapport with the patient.

Panic and a demoralised feeling is common for the surgeon too after encountering a complication. Emotional support can often be got from family, friends and mentors and this should be sought for and gratefully accepted. It is important to recover soon from the low after a complication and bounce back. Mentors are an important source of help for advice as well, and it is always important to give thanks to them.

Post-procedural review and analysis to see if the complication could have been avoided or tackled in a faster/ better way is important and this leads to a process of constant self-improvement.

To conclude: do not get disheartened by complications. There is a learning curve for everyone with published data for various procedures. Go step by step to improve your skills. Remember, Rome was not built in a day. And always, even with terrific results, there will be some unhappy patients, as well as deeply grateful ones with suboptimal results.

Dr Soosan Jacob is Director and Chief of Dr Agarwal’s Refractive and Cornea Foundation at Dr Agarwal’s Eye Hospital, Chennai, India and can be reached at dr_soosanj@hotmail.com