Cornea

Knowing Iris Repair: Post-Therapeutic PK for Corneal Ulcer

Challenging path lies ahead for corneal ulcer patients seeking visual rehabilitation after this common indication.

Soosan Jacob

Published: Wednesday, May 1, 2024

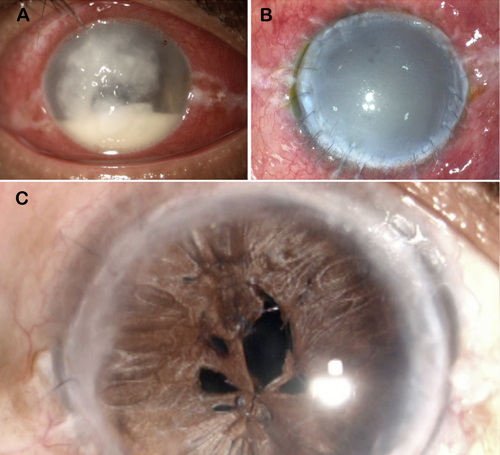

Corneal ulcers are a common presentation in both the developed and the developing world. It can be very devastating, resulting in the loss of the eye. Intense medical management is required, often indicating a therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty (TPK). Done in an acutely infected and inflamed setting, a TPK aims to remove the bulk of infection.

Preventing infection in the new graft needs intense medications postoperatively. Recovery from TPK depends on the extent of initial infection, pathogenic organism, type and extent of surgery, postoperative medications, antibiotic sensitivity, systemic and ocular conditions, etc. Surgery can sometimes be unpredictable, and an increased risk of expulsion of lens and vitreous exists, especially if the infection involved a large extent of the cornea, necessitating large-diameter host trephination. Any breach into the posterior segment can result in the introduction of the pathogenic organism into the vitreous cavity with resultant endophthalmitis. Even if surgery is completed successfully, reinfection of the graft can necessitate a repeat therapeutic keratoplasty.

The prognosis is not always bleak, however. A therapeutic graft can often clear infection and save the eye. In fact, the primary aim of a successful TPK is only infection clearance and not visual rehabilitation. Therefore, following successful recovery from a TPK, the patient often has an oedematous and failed graft—usually vascularised because of intense postoperative inflammation, lack of steroids, and sometimes inadvertent retention of loose sutures. Fibrin and exudates in the anterior chamber (AC) are common postoperatively, and these may resolve, leaving extensive peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS) in their wake, which can result in angle closure glaucoma.

The path forward for these patients includes secondary surgery for visual rehabilitation. Surgery can be complex and involve combined surgeries, even multiple surgeries, with most cases requiring anterior segment reconstruction. Anterior segment OCT is helpful preoperatively to understand the AC characteristics since the opaque graft may not allow visualisation of AC details through the slit lamp.

Many problems need to be tackled:

Neovascularisation

This is a risk factor for graft rejection and should be treated preoperatively. Topical anti-inflammatories such as steroids help in the regression of new vessels. Various techniques have been described, such as fine needle diathermy, where a needle is passed through the area of neovascularisation and cauterised. Localised collagen shrinkage is, however, a disadvantage.

Mitomycin intravascular chemoembolization (MICE) for regression of new vessels has recently gained traction—although difficult cannulisation, inability to treat very small vessels, and use of MMC are some disadvantages. Topical, intrastromal, sub-Tenon, and (if required) intracameral anti-VEGF injections and argon green laser photocoagulation are other tried methods, but cost, limited efficacy, and difficulty are disadvantages.

Cataract

Co-existing cataract needs to be extracted, but visibility is often very low. Trypan blue and the endoilluminator may be used for improving visualisation. Muscle memory also plays a major role during manoeuvres with suboptimal view. A hydrophobic IOL is preferred to avoid opacification from the air tamponade used in endothelial keratoplasty.

Secondary IOL implantation

This may be required if the crystalline lens or an IOL were expelled during the therapeutic keratoplasty or if a PCR occurred during cataract extraction. Sulcus placement is done with optic capture when anterior capsular support is good and a glued IOL, Yamane, or iris fixation if capsular support is insufficient. At Dr Agarwal’s Eye Hospital, the preference is a glued IOL due to good stability provided by the haptic tuck within intrascleral Scharioth tunnels.

Peripheral anterior synechiae

PAS can be a cause not just for angle closure glaucoma but also for future graft rejection and must be released, which may be done simply with viscoelastic or may involve a combination of sharp and blunt dissection. Fibrotic, atrophic, and often friable iris can lead to stromal or pupillary tears. Different combinations of iris repair—such as single-pass four-throw pupilloplasty, iridodialysis repair, and iridodiathermy—may be utilized, although bleeding and increased postoperative inflammation may occur. The final reconstructed iris may continue to have tears or appear distorted because of poor iris tissue availability. Though not of cosmetic concern in darker irides, this may be concerning in lighter irides. In addition, stray light or photophobia from central iris defects may cause visual symptoms such as photophobia, glare, or starbursts. Simple solutions are tinted glasses, coloured cosmetic lenses, or even iris prosthetic devices.

Iris fibrosis dissection

Fibrotic membranes over the iris are common and may result in a distorted pupil and inability to move the iris sufficiently for pupilloplasty. Such membranes can be removed with dissection using a 23-gauge needle to create a plane, followed by the combined use of microscissors or vitrector.

Pupil

Pupilloplasty corrects pupillary distortion by making the pupil small and the iris diaphragm taut to help prevent PAS reforming. Making the aperture small enough for a pinhole effect can also help tackle irregular astigmatism from a penetrating keratoplasty by cutting off peripheral light rays and decreasing the effect of higher-order aberrations. Iridodiathermy, as previously described, flattens the iris and allows better air fill for endothelial keratoplasty.

Ahmed glaucoma valve (AGV)

In case intraocular pressure is increased, an AGV may be required. If being combined with endothelial keratoplasty, the valve plate is first sutured before creating a 5x5 mm scleral flap, followed by other steps such as cataract surgery, iridoplasty, etc. The tube is then trimmed and inserted in the posterior chamber behind the iris and in front of the IOL for visibility just beyond the pupillary border. The endothelial keratoplasty is finally performed, and, if required, a temporary tube ligation suture applied.

Endothelial keratoplasty

Our hospital prefers a pre-Descemet’s endothelial keratoplasty (PDEK) for these cases because of the unique advantages this provides. Such eyes are complex, and Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty is difficult because of difficulties in graft unfolding and centring and a higher risk of detachment. The air pump-assisted technique allows PDEK to be performed with ease since graft decentration and extreme edge folds can be easily corrected. Infusion of pressurised air also decreases the risk of graft detachment. In addition, a PDEK graft is easily amenable to other manoeuvres such as trans-graft suturing. Complete clarity can be recovered in the old TPK graft stroma with excellent visual results, especially in well centred and large grafts. Decentred TPK grafts or those with large amounts of irregular astigmatism may benefit from a repeat penetrating keratoplasty or a PDEK combined with pinhole pupilloplasty. Graft rejections have an increased risk, and therefore close follow-up, medication compliance, pre-/intraoperative treatment of neovascularisation and inflammation, and surgical correction of PAS are important. If the graft does reject, repeat endothelial keratoplasty is possible, though extensive corneal or iris neovascularisation may necessitate a Boston keratoprosthesis. Glaucoma should be watched for in these patients and managed according to its type and aggressiveness.

To conclude, treatment and visual rehabilitation for corneal ulcer can be a long path to travel, both for the ophthalmologist and the patient. But the results of these surgeries can be miraculous and very gratifying—gifting vision once again to patients who were blind in the eye.

Soosan Jacob MS, FRCS, DNB is Director and Chief of Dr Agarwal’s Refractive and Cornea Foundation at Dr Agarwal’s Eye Hospital, Chennai, India, and can be reached at dr_soosanj@hotmail.com.

Latest Articles

Organising for Success

Professional and personal goals drive practice ownership and operational choices.

Update on Astigmatism Analysis

Is Frugal Innovation Possible in Ophthalmology?

Improving access through financially and environmentally sustainable innovation.

iNovation Innovators Den Boosts Eye Care Pioneers

New ideas and industry, colleague, and funding contacts among the benefits.

José Güell: Trends in Cornea Treatment

Endothelial damage, cellular treatments, human tissue, and infections are key concerns on the horizon.

Making IOLs a More Personal Choice

Surgeons may prefer some IOLs for their patients, but what about for themselves?

Need to Know: Higher-Order Aberrations and Polynomials

This first instalment in a tutorial series will discuss more on the measurement and clinical implications of HOAs.

Never Go In Blind

Novel ophthalmic block simulator promises higher rates of confidence and competence in trainees.

Simulators Benefit Surgeons and Patients

Helping young surgeons build confidence and expertise.