Cataract, Refractive, IOL, Refractive Surgery, Eye on History

A Second Look at the First IOL Implantation

The traditional hero and villain story might not have a bad guy after all.

Sean Henahan

Published: Monday, September 2, 2024

The invention and implantation of the first IOL by Dr Harold Ridley has become the stuff of legend. Every good story needs a villain, and in this case, that role was filled by Dr Stewart Duke-Elder (1898–1978).

But it may be this villain got a bad rap, according to Robert Maloney MD, who recently spent six months on sabbatical at Oxford University researching the early days of cataract surgery. EuroTimes Editor-in-Chief Sean Henahan interviewed Dr Maloney about his work.

This year, we are marking the 75th anniversary of the first IOL implantation by Dr Harold Ridley. You are known to be a historian of ophthalmology—could you tell us about your recent investigations?

I pursued a six-month research project on Drs Ridley and Duke-Elder while on sabbatical at Oxford University. I’ve been going through archives at Moorfields Eye Hospital and the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology in London, digging through old records and trying to better understand the invention of the IOL.

What have you found? What was cataract surgery like, implanting the first IOL before phacoemulsification, viscoelastics, even operating microscopes?

You can watch the original video of Ridley’s first IOL implantation on YouTube. The first procedure is mildly terrifying from a modern point of view. It was done with loupes, using a 180-degree corneal-conjunctival section, suture pulling at the cornea, a giant PMMA lens inserted. It makes you want to look away. You don’t know what’s happening to the cornea, don’t know what’s happening to the iris, or where the vitreous is. It is amazing they did as well as they did back then. They didn’t do that well by our modern standards, but they still did pretty well. Some got lucky, with the IOL staying in place, but some didn’t get lucky. This is one area of my research—looking at the complication rates of the early procedures with the Ridley lens.

How was this initial work with IOLs received by the ophthalmology establishment?

Harold Ridley thought up the idea of a lens implant and put it in a patient either in November of 1949 or February of 1950. There is still some debate about the date. He did 8 patients in 17 months. He then presented his work—a secret until then—at the Oxford Ophthalmological Congress.

Stewart Duke-Elder was the Director of Research at the Institute of Ophthalmology in London and probably the leading ophthalmologist in the world at that time. He refused to look at the two patients Ridley brought to the conference. He allegedly walked out with his acolytes behind him, which, in retrospect, seems petulant and small minded. According to Dr Richard Packard, Duke-Elder threatened a young Peter Choyce (who would become an early pioneer of IOL surgery) that if he helped Ridley with his implant, he would not recommend Choyce for a job.

Duke-Elder is viewed as the evil character here, suppressing a brilliant young inventor who made a world-changing invention. He has really come down through history as the devil in this story. My research has been about who Duke-Elder really was and why he reacted the way he did. I’ve come away with a much more sympathetic view of Duke-Elder than when I started this project. He was the son of a Scottish Presbyterian minister who practised a by-the-book, rules-oriented religion. Duke-Elder was an outsider. His original surname was Duke, but he wanted a hyphenated name to suggest nobility, so he added his mother’s surname to create ‘Duke-Elder.’ He went to London and trained as a surgeon, became the oculist to the royal family (a very high position in ophthalmology), and was knighted at age 35, which is rare.

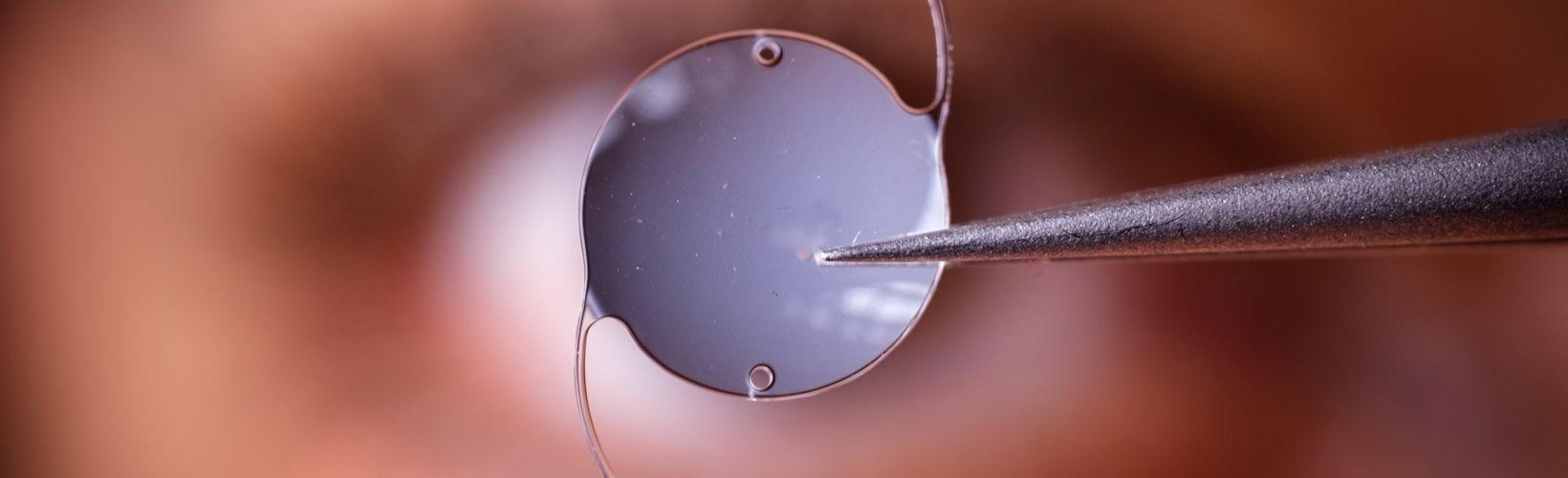

Duke-Elder worked his way up from modest beginnings by following the rules and doing everything in the right manner. Ridley came along with a clever idea, but he did it with no animal testing and no lab research. Ridley designed this IOL in the front seat of his Bentley, working with John Pike from Rayner & Keeler—designing a huge IOL the same size and shape as the human lens with no haptics. Ridley implanted the IOL, and the first patient turned out with a refraction of -20 D. He got the IOL power completely wrong because he didn’t research the index of refraction of PMMA and had no idea how to fixate these lenses. He figured if he made the implant the same size as the human lens it might stay there. It didn’t. The PMMA material he used was sterilised with a chemical that resulted in a lot of inflammation. Because Ridley did not do animal testing, patients suffered.

During this time, Duke-Elder ran a research institute with a lab for physiologic optics on the third floor, perfect for determining the power of an IOL. The Institute also had a beautiful set of research facilities for working with rabbits and dogs.

From Duke Elder’s point of view, he saw an invention developed in secrecy and not tested prior to use that caused significant harm to patients. Duke-Elder didn’t have the benefit of hindsight. Who can blame him for saying IOLs were a bad idea? Duke-Elder was not the evil character in this story. In fact, Ridley’s lens implant never really worked. It was the people who came later who invented IOLs with haptics that finally worked. Ridley made a big contribution. Duke-Elder was the person who said there was a more responsible way to develop IOLs.

Did Duke-Elder ever join the IOL camp?

He never came around. At Moorfields in the 1970s, there were two types of eye surgeons: those who put in IOLs and those who took them out. Moorfields was the referral centre for the whole country and saw a significant volume of problem cases associated with early IOLs. This included corneal decompensation, angle closure, and dislocated lenses. It gave the surgeons at Moorfields a slanted viewpoint because happy patients didn’t come in for a second opinion.

Duke-Elder died in 1978. Remember, we didn’t have a safe lens implant until Shearing invented the J-loop posterior chamber lens in 1978. It wasn’t until 30 years after Ridley put in his first lens that we finally had a lens that was safe to use and would become widely accepted.

Robert Maloney MD, MA (Oxon) is a former Professor of Clinical Ophthalmology at the Stein Eye Institute of the University of California, Los Angeles, US. He is the Chairman of the Board of the American-European Congress of Ophthalmic Surgeons (AECOS). He was managing partner of the Maloney-Shamie Vision Institute and Chief Medical Officer of RxSight, the company that developed the light adjustable IOL.