Cornea, Corneal Therapeutics, Issue Cover

From Lab to Life: Corneal Repair Goes Cellular

Long-awaited cellular therapies for corneal endothelial disease enter the clinic.

Dermot McGrath

Published: Monday, April 1, 2024

“ The patient is then able to resume normal activities of daily living. Vision begins to return quickly. “

Cellular therapies for corneal endothelial disease—once limited to the realm of laboratory studies and experimental research—are taking the first steps into clinical practice. Following successful initial trials, cell-based therapies carry the promise of greater sustainability and a treatment accessible to general ophthalmologists with the potential to alleviate the growing demand for corneal transplantation.

Several companies are at the forefront of the new frontier in tissue regeneration. Aurion Biotech has already received regulatory approval in Japan for its cellular injection therapy for bullous keratopathy and is pursuing phase 1/2 studies in the United States. Emmecell has successfully completed phase 1 studies in the United States to treat corneal oedema secondary to corneal endothelial dysfunction.

Another company, Cellusion Inc, has partnered with Keio University in Tokyo, Japan, in the first trials of induced pluripotent cell-derived corneal endothelial cell substitutes for bullous keratopathy in three participants. The technology has just been granted orphan drug designation by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ahead of further clinical trials. Numerous research projects are also underway worldwide to develop cellular treatments that could mitigate or eliminate the need for corneal transplantation to treat a range of endothelial diseases.

Much of the pioneering research in utilizing cultured human corneal endothelial cells (HCEC) for transplantation has been conducted by Professor Shigeru Kinoshita’s group at Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan. Although primary CECs have a limited capacity for in vitro expansion, Prof Kinoshita’s breakthrough innovation uses a Rho-kinase inhibitor to promote cell proliferation and enable the injection of mature-differentiated endothelial cells derived from young donor allogeneic cells directly into the anterior chamber.

With this technique, one donor cornea theoretically makes it possible to create enough CHCECs for 300 eyes or more. To hasten its clinical and commercial development, Prof Kinoshita licensed the cell-injection technology to US company Aurion Biotech, which subsequently carried out further trials in Japan and El Salvador, confirming the therapy’s safety and efficacy. In early 2023, Aurion obtained regulatory approval from Japan’s Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) for bullous keratopathy treatment—the first-ever regulatory approval for an allogeneic cell therapy to treat corneal endothelial disease.

Aurion also began phase 1/2 trials in the United States in autumn 2023, aiming to recruit 100 patients with corneal oedema secondary to corneal endothelial dysfunction, with study completion expected before the end of 2025. Overall, the CHCEC injection procedure has now been carried out worldwide in more than 130 patients for a variety of indications—including Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD), pseudophakic bullous keratopathy (BK), and corneal endothelial failure after penetrating keratoplasty—with patients experiencing consistent, clinically meaningful, and sustained improvements in key measures of corneal health, according to investigators associated with the trials.

“I have been privileged to examine the eyes of some of Professor Kinoshita’s patients, and their corneas and cell counts are amazing,” said Edward Holland MD, Director of Cornea at the Cincinnati Eye Institute and Professor of Ophthalmology at the University of Cincinnati. Dr Holland, who serves as Chair of the Medical Advisory Board at Aurion Biotech, called the therapy “a truly once-in-a-lifetime occurrence” and said he was optimistic about it becoming the standard of care and expanding the ability to treat many more patients who suffer from corneal endothelial diseases.

Core advantages

Dr Holland cited several core advantages of corneal endothelial cell therapy (CECT) compared to current endothelial keratoplasty (EK) techniques.

“This is a less invasive procedure for the patient,” he explained. “We make a small incision to ‘polish off’ diseased endothelial cells, then inject healthy culture endothelial cells into the anterior chamber. The patient lies face down for a few hours to allow the cells to settle into place and adhere to Descemet’s membrane. The patient is then able to resume normal activities of daily living. Vision begins to return quickly. This procedure eliminates the requirement of positioning the patient on their back for 24 to 48 hours, which is quite uncomfortable and sometimes not possible for many patients.”

CECT also eliminates the problem of EK detachment, which still occurs at a significant rate and results in another procedure for patients and risk of endothelial cell loss, Dr Holland pointed out.

“Studies show the postoperative endothelial cell count will be significantly higher with CECT compared to EK surgery, likely leading to a longer success rate and reduction in the need for additional endothelial replacement.”

The results also seem sustainable in the long term. In 2021, Prof Kinoshita’s group published the five-year outcomes of the first 11 patients treated in Japan for endothelial failure, reporting no serious adverse events and significant, lasting improvements in central corneal thickness and best-corrected visual acuity.

Donor shortages

One of the most compelling arguments in favour of cellular injection therapy is the implications it holds for the global shortage of donor corneas. Corneal blindness is the second most common cause of blindness worldwide, with treatment limited by the number of donors available for transplant.

The shortage of corneas results in more than 40,000 visually impaired people waiting for corneal transplants every year in Europe alone, with 10 million untreated corneal blindness patients globally and 1.5 million new cases of corneal blindness annually.

Although CECT does not completely obviate the need for donor tissue, Dr Holland believes it may still go a long way towards easing the problem associated with donor shortages.

“A recent JAMA Ophthalmology survey indicated that for every 70 diseased eyes, there is only one donor corneal available for transplant,” he said. “With corneal endothelial cell therapy, we can potentially produce 1,000 doses or more of fully differentiated human corneal endothelial cells from a single donor. For the first time ever, we have the means to produce enough cells to treat everyone with this disease.”

Dearth of skilled surgeons

According to Ellen Koo MD, Associate Professor of Ophthalmology at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami, and Principal Investigator of Emmecell’s clinical trial of injected magnetic human corneal endothelial cells, “the shortage of donor corneas globally is due, in part, to lack of eye-banking access in emerging countries. Additionally, there are not enough skilled corneal transplant surgeons in many parts of the world, and effective and wide-scale skills-transfer of keratoplasty surgical techniques remains an ongoing challenge.”

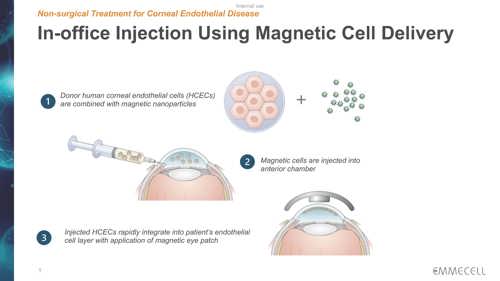

Emmecell’s twist on the injection therapy is to add biocompatible magnetic nanoparticles to cultured HCECs so the cells become magnetic. The treatment includes an external magnetic eye patch worn by the patient right after magnetic HCEC injection to facilitate cell adhesion and integration into the recipient cornea.

“One donor cornea can offer treatment for hundreds of patients, and the general ophthalmologist may be able to provide this treatment without needing to take the patient to the operating room,” Dr Koo said. “Additionally, the patient may be treated at earlier disease stages.”

Emmecell’s six-month safety and tolerability outcomes for 21 patients with corneal oedema secondary to Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy were recently reported in trials at six US centres. Patients received magnetic nanoparticles in one of four doses: 50,000; 150,000; 500,000; or 1,000,000 cells via a single intracameral injection. Some patients received concurrent Descemet stripping or endothelial brushing right before injection, while others were in the injection-only group.

“There were no investigational treatment-related adverse events, nor did we observe issues related to intraocular inflammation or increased intraocular pressure,” said Dr Koo. “Of note, we saw a dose-dependent effect on the continued improvement in vision—up to six months after injection. None of the subjects required surgery in the six-month follow-up period. We are also the first group to show that injection of endothelial cells without surgical intervention can improve vision in subjects with Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy.”

As the next step in the trial, a randomized, double-masked study has commenced at 10 centres in the United States to establish the optimal therapeutic dose.

The European angle

With Japan and the United States setting the pace in cellular therapies, the concern is that European patients may have to wait considerably longer to benefit from these groundbreaking treatments.

“It’s not particularly surprising that the companies working on primary cultured corneal endothelial cell therapies are currently mostly active in the United States,” remarked Mor Dickman MD, PhD, professor of ophthalmology at Maastricht University, Netherlands. “The United States is a big market, and the price they can expect for such a product in the United States is higher than in Europe, where the healthcare systems work differently. Also, the regulatory pathway, which was traditionally much more difficult in the United States, has somehow become more straightforward in the United States and more cumbersome in Europe.”

Dr Dickman also noted there are challenges specifically related to Europe in terms of cell therapy application.

“Most of the patients treated in Japan had bullous keratopathy, so they did not have guttae on the Descemet’s membrane. In the protocol employed, Descemet’s membrane was not removed. For those patients with Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy treated by cell injection, the guttae were still visible on Descemet’s membrane years after the treatment,” he said. “We know the guttae themselves will cause stray light and other complications, [which] is particularly relevant in [a European] context, where between 70% to 80% of our transplants are for Fuchs’ disease.”

Looking further ahead, Dr Dickman said he is excited about the potential of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) for treating a range of ocular diseases, as they possess self-renewal capabilities, can be derived from adult somatic cells, and can be differentiated into all cell types including CECs.

While many technical and regulatory hurdles remain before bringing iPSC cell therapies into the clinic, Dr Dickman remains guardedly optimistic for the future.

“For iPSCs, we are still mainly in the research and development phase compared to the corneal endothelial cultured primary cells, which are more advanced in terms of technology readiness level,” he said. “The questions for these therapies are more related to regulatory approval in different markets, pricing strategies, and identifying who will benefit most from their application.”

Edward Holland MD is Director of Cornea at the Cincinnati Eye Institute and Professor of Ophthalmology at the University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio, United States. edward.holland@uc.edu

Ellen Koo MD is Associate Professor of Ophthalmology at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami, Florida, United States. exk126@med.miami.edu

Mor Dickman MD, PhD is Professor of Ophthalmology at Maastricht University, Netherlands. m.dickman@maastrichtuniversity.nl

Latest Articles

Towards a Unified IOL Classification

The new IOL functional classification needs a strong and unified effort from surgeons, societies, and industry.

The 5 Ws of Post-Presbyopic IOL Enhancement

Fine-tuning refractive outcomes to meet patient expectations.

AI Shows Promise for Meibography Grading

Study demonstrates accuracy in detecting abnormalities and subtle changes in meibomian glands.

Are There Differences Between Male and Female Eyes?

TOGA Session panel underlined the need for more studies on gender differences.

Simulating Laser Vision Correction Outcomes

Individualised planning models could reduce ectasia risk and improve outcomes.

Need to Know: Aberrations, Aberrometry, and Aberropia

Understanding the nomenclature and techniques.

When Is It Time to Remove a Phakic IOL?

Close monitoring of endothelial cell loss in phakic IOL patients and timely explantation may avoid surgical complications.

Delivering Uncompromising Cataract Care

Expert panel considers tips and tricks for cataracts and compromised corneas.

Organising for Success

Professional and personal goals drive practice ownership and operational choices.